The numbers behind the DACA program: how many people would its end affect?

Michael M. Santiago // Getty Images

The numbers behind the DACA program: how many people would its end affect?

Immigration advocates rally on 10th anniversary of DACA policy

2022 is the 10th anniversary of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, also known as DACA. It has recently been thrust into the spotlight as politicians—and courts—once again debate its legitimacy.

Earlier this year, the Department of Homeland Security ruled to preserve DACA for noncitizens who met specific criteria. However, in October, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals threw its status in limbo again as it ruled in favor of a lower court’s earlier ruling that DACA was illegal. For now, DACA recipients can renew their status, but the fate of new applicants is uncertain. The DHS continues to accept but not process new initial requests for DACA status.

To become a DACA recipient, a person must meet a number of different criteria. They must have arrived in the U.S. when they were under 16 years of age, and as of June 15, 2012, resided in the country for five contiguous years and be under 30 years of age. They must have been physically within U.S. borders on the day that the government announced the DACA program, as well as the moment they requested deferred action. They cannot have been convicted of serious crimes or considered a threat to national security. They must also have finished high school, earned a GED, or served in the Armed Forces and, if discharged, been discharged honorably.

The program does have some caveats. The main one is that although DACA can help to postpone deportation, it neither automatically nor subsequently ensures legalization or citizenship, and it doesn’t grant amnesty. Recipients cannot vote in U.S. elections or get government benefits such as Social Security, financial aid for college, or food stamps. Also, DACA recipients cannot leave the country without travel authorization, which the government will only grant for issues such as medical treatment, care of a family member, or for law enforcement or national security reasons.

As of June 2022, there are 594,120 people with active DACA status—all of whom would be displaced should the program end. Stacker looked into the numbers behind the current recipients of DACA status to find out just how many lives would be affected by its end, citing data from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the Department of Homeland Security, and the National Immigration Law Center.

You may also like: Former jobs of every Supreme Court justice

![]()

Stacker

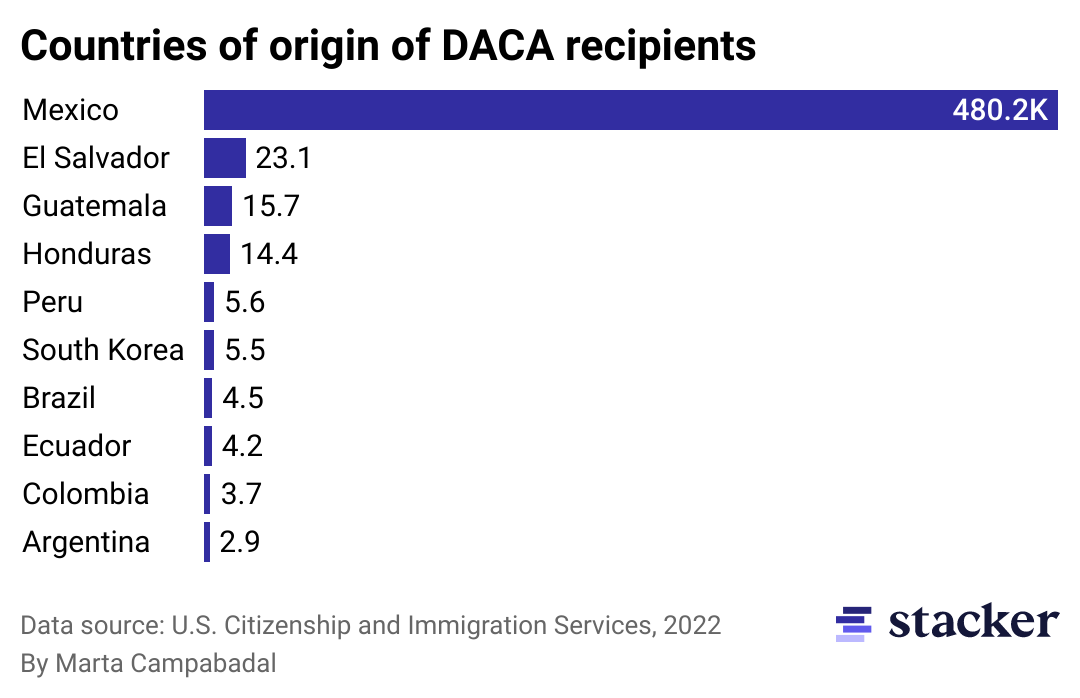

Although there are DACA recipients from more than 150 countries, a large majority come from Mexico and other Central American countries

Bar chart with the top 10 countries of origin of DACA recipients.

“Dreamers,” the nickname for DACA recipients popularized by the national media, are most often thought of as people coming from regions of the world riven by strife, conflict, or comparatively poor living conditions to those in America. The proximity of Mexico and Central America to the U.S. southern border makes Southern states logical destinations—but while that is true, states like California, Illinois, and New York also have some of the most significant numbers of DACA participants.

Illegal immigration is—like abortion and gun rights—one of the most fiercely debated and contested issues in the U.S. Most people who enter and live in the U.S. without authorization are from Mexico. In 2018, more than 50% of the 11 million undocumented citizens in the U.S. were native to Mexico. While the Mexican government is not presently embroiled in global-scale conflict such as that taking place in Ukraine, it has been involved for several years in armed conflict with two drug cartels.

People generally positively regard the quality of life in Mexico. Still, some social aspects may make its neighbor to the north an attractive alternative—the public education and health systems are relatively poor, and crime rates in many parts of the nation are high.

Stacker

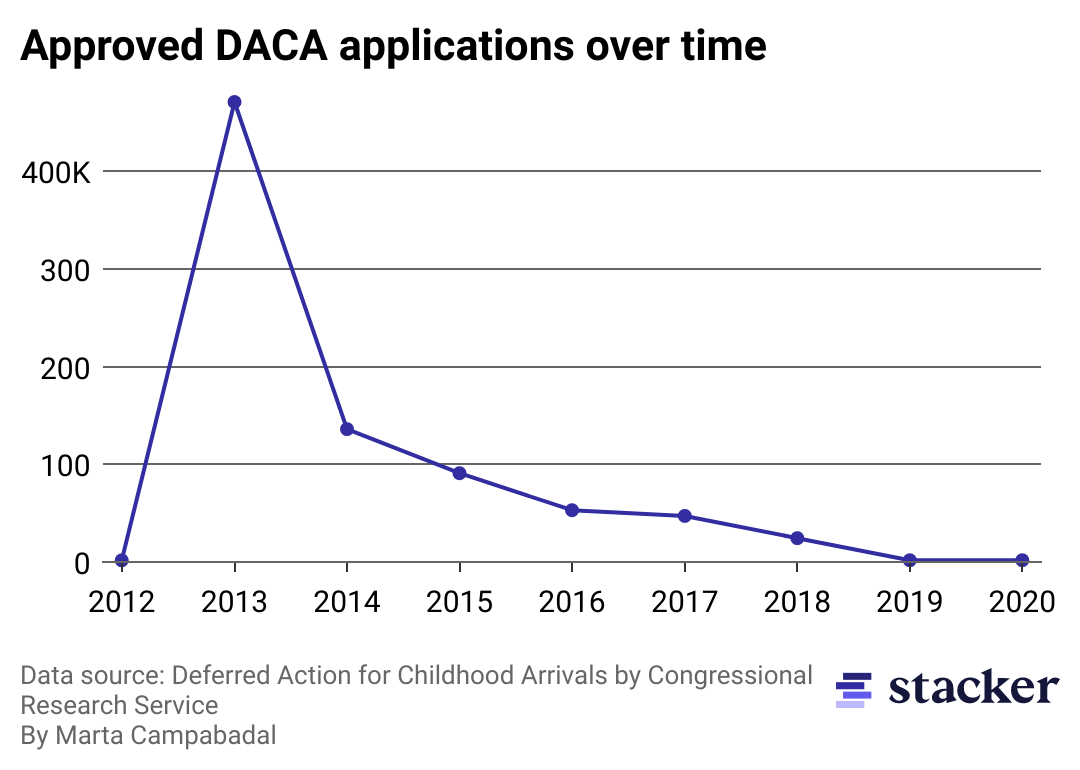

As years go by, fewer people meet DACA requirements

Line chart with DACA applications and renewals overtime.

Because applicants had to have arrived in the U.S. before they were 16 years of age and had to be under 30 on June 15, 2012, DACA applications have steadily dwindled over time because people are simply not eligible anymore or have already applied. Most filings are now renewals of status rather than new applications. Moreover, the Department of Homeland Security is continuing to block Citizenship and Immigration Services from processing initial applications.

Stacker

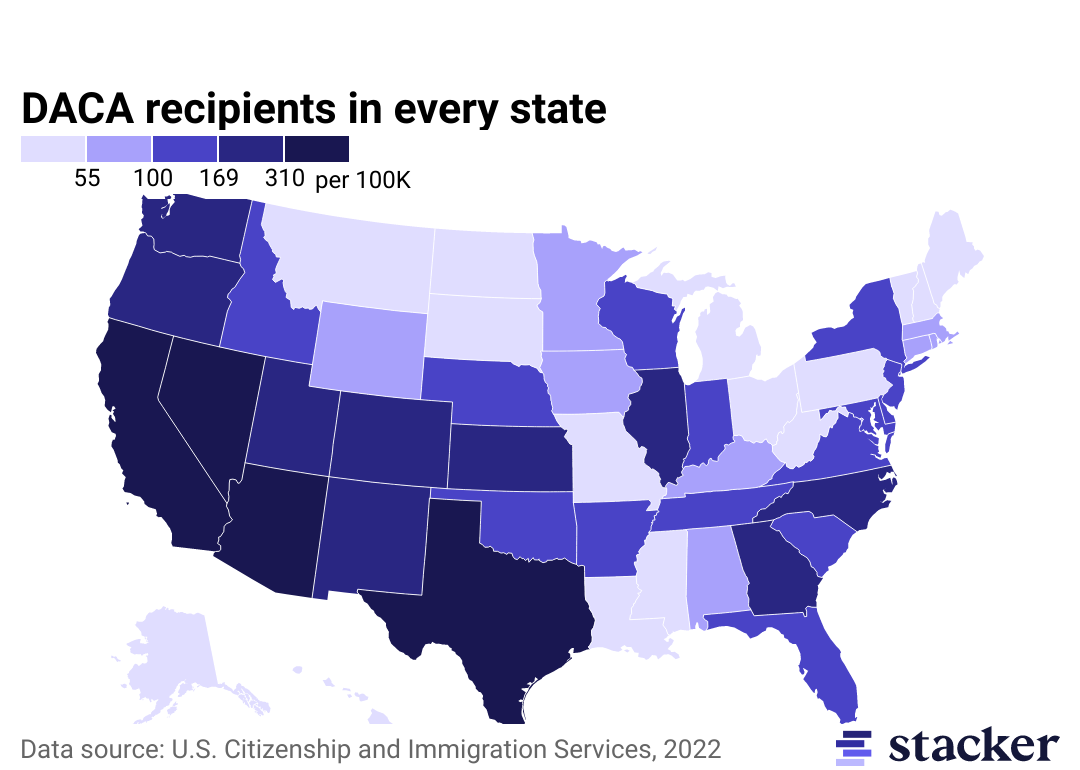

A majority of DACA recipients live in Western states

State map of the DACA recipients per 100,000 in every state.

The three states with the most DACA recipients per 100,000 people are California, Nevada, and Texas, which account for nearly half the total number of recipients nationwide. DACA recipients from California pay $3.1 billion in taxes yearly, including federal, state, and local taxes, and possess approximately $8 billion in spending power. In Texas, DACA recipients pay $1.2 billion in taxes yearly and own more than 11,000 homes across the state.

While the Southern and Western states count the most significant proportion of Dreamers, each state has DACA recipients living within its borders, meaning these individuals are impacting the economy and social makeup on a national level. Dreamers residing in Illinois, for example, hold $1.2 billion in spending power, which is nearly 10 times the entire 2022 budget for the city of Springfield, the state capitol.

Stacker

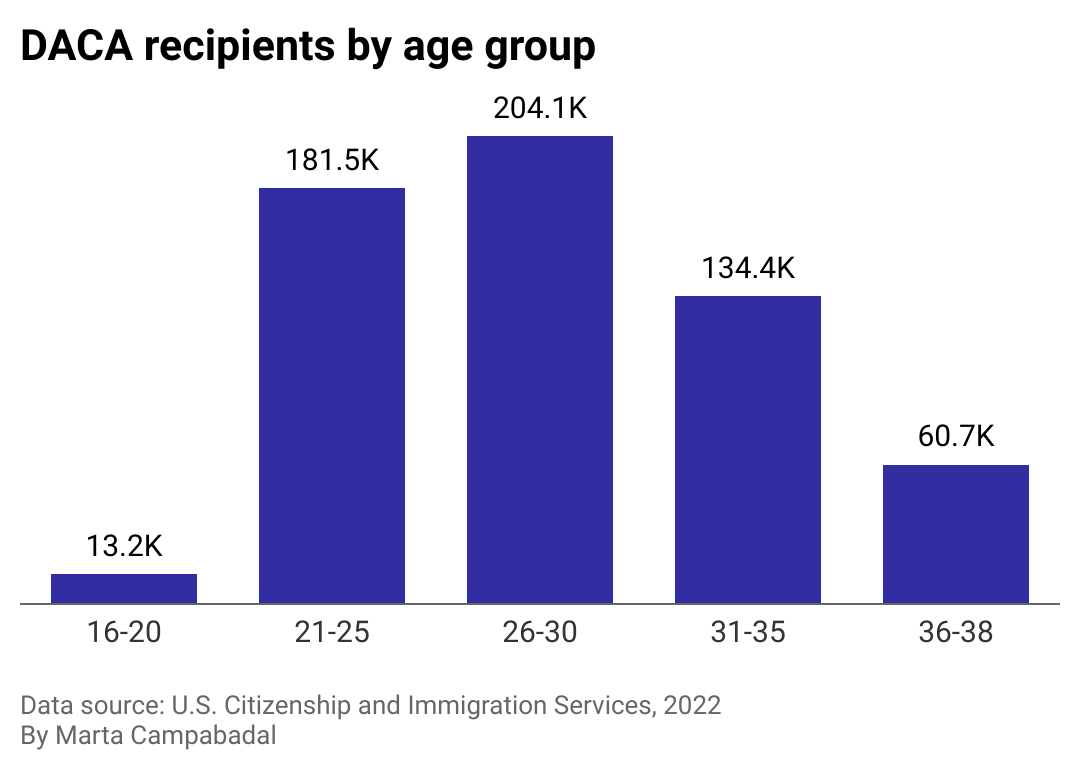

The majority of DACA recipients are in their 20s

Bar chart showing DACA recipients by age group.

A large number of people submitted DACA applications in 2012, many on behalf of minors. Consequently, more than 60% of all DACA protectees are now between 21 and 30 years old, with the average age being 28.

Of all DACA recipients, women represent about 53%, and men 46%. Most of them—70%—are single, while 26% are married. This last number is significant because the young Dreamers of 2012 are now moving into the next phase of their lives—getting married, starting families of their own, and purchasing homes.

This is all to say that, regardless of the legal and political maelstrom still swirling over the program that allowed them to stay in America, Dreamers are now demonstrably contributing to the “American way of life.”

You may also like: Cities before conflict: what it was like to visit Juarez, Tehran, and 13 other afflicted places