What’s behind the growing number of manufacturing jobs?

Canva

What’s behind the growing number of manufacturing jobs?

Two workers in a manufacturing plant.

In the years since the COVID-19 recession of early 2020, manufacturing jobs in the U.S. have recovered quicker than ever seen in modern history.

Peaking in 1979, U.S. manufacturing reached something of a precipice in the 1980s.

The U.S. remained a goods-producing country. While output was relatively steady, fewer Americans were employed to mine metals, assemble automobiles, and piece together military technology for the defense sector by the decade’s end.

But from the mid-20th century through 2000, America was shedding jobs in manufacturing and gaining jobs in its service sector—now a hallmark sector of the country’s economy next to its highly advanced tech sector.

The 1980s kicked off with dual recessions—not unlike today’s trying economic conditions stoked by a war of resources abroad and tightening monetary policy aimed at combating high inflation. Where manufacturing work represented almost 1 in 3 jobs in America at the time, by 1982, the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression had devastated goods-producing jobs.

The manufacturing sector accounted for an outsized 90% of the job losses, according to historical Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The biggest losses at the time were suffered in the mining industry, where 3 in 5 workers with jobs related to extracting critical resources such as iron and copper were laid off.

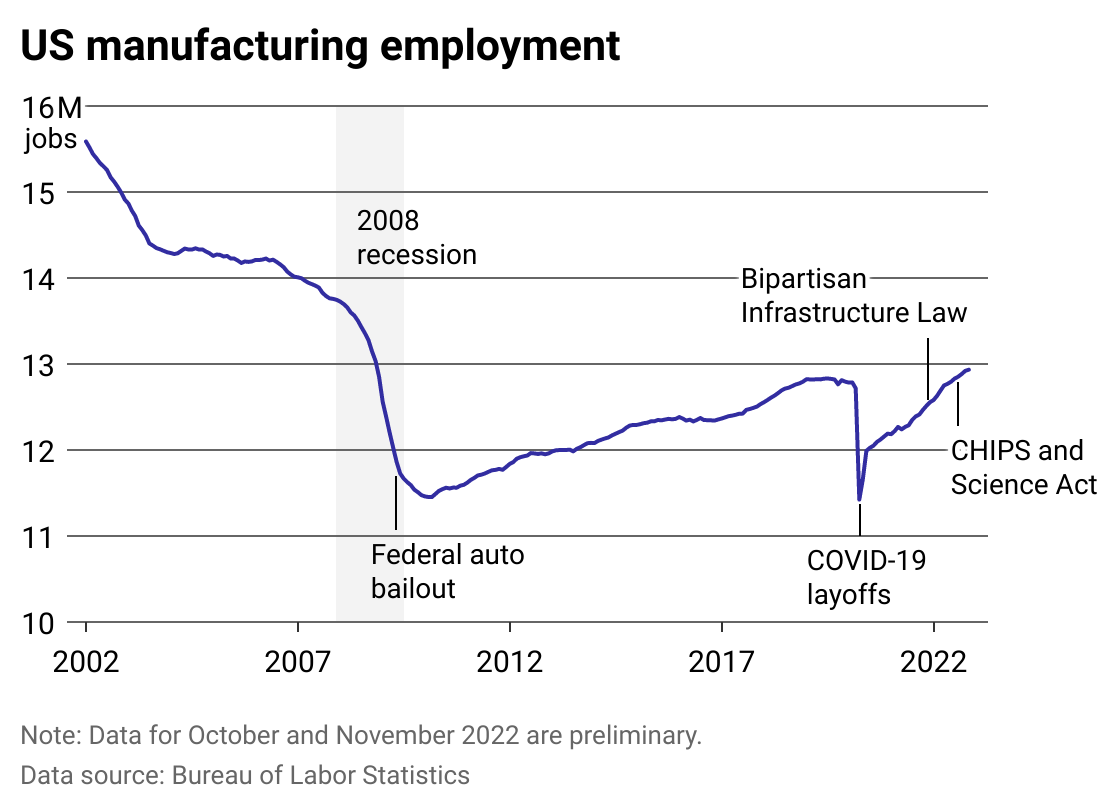

Today, manufacturing employment is well below the nearly 20 million it reached in 1979. But jobs reached nearly 13 million based on preliminary data for November 2022—more than recovering from the COVID-19 slump and reaching the highest level of employment in the sector since 2009.

How did the U.S. manage it, and is the country amid a new era for domestic manufacturing?

Get It Made analyzed BLS Current Employment Statistics data to look at the recent surges in manufacturing employment and charted those against a timeline of events that have contributed to more manufacturing jobs being added over the past decade. The BLS data is based on a survey, so true employment values may vary.

![]()

Get It Made

Manufacturing jobs exceed pre-COVID levels

Line chart showing manufacturing employment over time, which has dipped significantly since the early 2000s and earlier but is trending up.

In previous economic cycles, the U.S. manufacturing industry has lost jobs during recessions only to gain them back afterward—but with the caveat that jobs have never returned to pre-recession levels. This was true of manufacturing job losses in the 1980s.

The challenges facing the U.S. workforce in 1980—manufacturing representing a major portion—are numerous, according to Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Thomas A. Kochan. They involve the globalization of business, greater competition from other countries in the automotive and metal industries, technological advancements that allow fewer workers to produce the same goods, and the relative affordability of outsourcing manual labor to countries like China with weaker currencies.

The challenge facing manufacturers in the COVID-19 recession was slightly simpler: Business leaders were uncertain when Americans would return to spending money as the virus spread.

But that fear dissipated when the government stepped in with expanded unemployment benefits for workers, stimulus payments, and forgivable payroll loans for businesses. Consumer spending roared back to life by the end of 2020, and Americans were hungry for goods rather than services. They weren’t just snapping up the medical masks many manufacturers pivoted to producing in spring 2020 but also furniture, vehicles, and homes.

John Gress Media Inc // Shutterstock

Federal auto bailout and post-recession recovery

An assembly line at an auto manufacturing plant.

Part of what made the Great Recession of 2008 so great, so to speak, was the depth and prolonged nature of the crisis. Job recovery was steady in the aftermath but slower than in previous recessions. It might have been slower if the U.S. had not provided $80 billion in capital to bail out the big American auto manufacturers. One study placed the jobs saved as a result of the stimulus at 1.5 million.

The years that followed are considered the recovery, which led up to the 2020 recession. Consumer demand slowly returned as Americans rebuilt their credit scores and made big purchases—like a new vehicle—they may have otherwise put off during the recession. That helped support jobs in manufacturing for American workers assembling the latest and greatest trucks and SUVs.

Evgenia Parajanian // Shutterstock

Pandemic relief legislation

A stimulus check from the pandemic.

When the U.S. entered this most recent COVID-19-induced recession, manufacturing jobs were impacted comparably to other industries. Car manufacturing stopped almost overnight, as leading automakers shut down assembly plants in the spring and dealerships closed their doors. In food production, meatpacking plants shuttered operations as workers fell ill and news reports about worker deaths percolated on cable news.

The rebound, however, was swift.

Most economists attribute the quick rebound in employment to massive aid packages passed by Congress. The U.S. government issued $4.5 trillion in total pandemic aid, with the biggest tranches going to agencies dealing with employment—the Small Business Administration and the Department of Labor. It funded forgivable loans for payroll, expanded unemployment benefits, and tens of millions specifically aimed at getting manufacturers back to producing goods.

Chip Somodevilla // Getty Images

Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and CHIPS and Science Act

US President Joe Biden signing the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 during a ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House on Aug. 9, 2022, in Washington DC.

A couple of bipartisan laws enacted in the aftermath of the COVID-19 recession offer a guide to where manufacturing employment is headed in the next several years.

Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021 and the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs act will infuse the manufacturing sector with an unprecedented $550 billion in capital through 2026 to build and repair bridges, roads, highways, rural internet infrastructure, and water treatment facilities.

The CHIPS and Science Act aims to rejuvenate the U.S. manufacturing sector to compete with foreign nations like China and keep the supply of critical goods like computer chips stable for American consumers. A shortage of computer chips at the start of the pandemic stymied manufacturing supply chains for everything from computers to automobiles.

When the CHIPS act was passed, the CEO of a New York-based automotive parts manufacturer expressed relief, saying, “For years, my industry has been at the mercy of the supply chain.”

This story originally appeared on Get It Made and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.