John Roberts has a united court on Trump. Now comes the hard part

Originally Published: 09 FEB 24 05:00 ET Updated: 09 FEB 24 09:14 ET By Joan Biskupic, CNN Senior Supreme Court Analyst

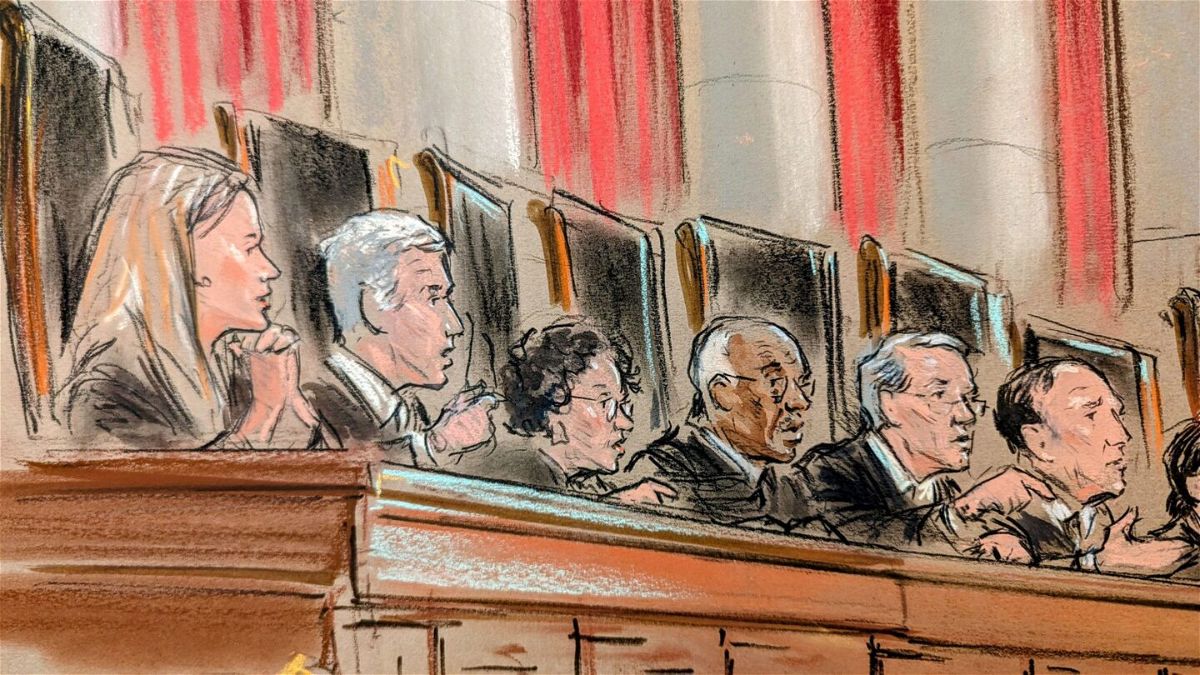

(CNN) — Soon after John Roberts took his seat at the center of the Supreme Court bench on Thursday, the cadence of the justices’ questioning suggested the chief justice would have an easy majority, if not unanimity, to reverse a Colorado ruling that blocked Donald Trump from the ballot.

Roberts had no need to engage in his own persuasive efforts from the bench, as often happens, to subtly begin corralling colleagues. They were with him.

A tone of political expediency and comity replaced the usual ideological divisions on this bench of six Republican-appointed conservatives and three Democratic liberals.

Still, now comes the hard part.

How quickly can the nine justices agree on some legal grounds and produce an opinion that ends the national uncertainty over whether states may bar Trump from ballots under a 14th Amendment section targeting insurrectionists?

Primary election contests are underway, and Super Tuesday is a month away.

Not since the 2000 case of Bush v. Gore has the Supreme Court been in the middle of an election battle of such potential magnitude. The courtroom was packed Thursday. Several of the justices’ spouses, including Jane Roberts, wife of the chief justice, sat in a special guest section. Lawyer Mark Paoletta, a close friend of Justice Clarence Thomas and his wife, Ginni, was also in the prime guest section.

Scores of reporters filled the usual press seats as well as overflow sections behind marble pillars. CNN and other news outlets carried the live-streamed audio of the arguments.

Any real possibility that the leading Republican presidential candidate would be kept off state ballots dissolved early in the hearing that ran slightly more than two hours. Roberts’ criticism of the Colorado Supreme Court decision barring Trump was echoed by his colleagues, even as they varied in their constitutional grounds.

The justices seemed united in apprehension for the practical consequences of removing a candidate from the ballot and revealed a concern for the politics of the day, which the chief justice often says they eschew.

Addressing lawyer Jason Murray, representing the Colorado voters who began the case, he said, “Counsel, what do you do with what would seem to me to be plain consequences of your position? If Colorado’s position is upheld, surely there will be disqualification proceedings on the other side. And some of those will succeed.”

Putting it more plainly, Roberts added, “I would expect that a goodly number of states will say, whoever the Democratic candidate is, you’re off the ballot. And others for the Republican candidate, you’re off the ballot.”

Murray began to respond, “Well, certainly, your honor, the fact that there are potential frivolous applications of a constitutional provision isn’t a reason –”

Roberts cut him off, saying, “Well now, hold on. You might think they’re frivolous but the people who are bringing them may not think they’re frivolous. Insurrection is a broad, broad term.”

Looking for grounds to side with Trump

In dispute is the 14th Amendment’s Section 3 that dictates, “No person shall … hold any office … under the United States … who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States … to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.”

The Colorado Supreme Court ruled in December that Trump should be disqualified under the provision because of his part in the January 6, 2021, attack on the US Capitol as he was fighting the valid results of the 2020 election that gave Joe Biden the White House.

In appealing that decision, Trump’s lawyer Jonathan Mitchell cited multiple grounds, among them that by the original terms of the provision, the president is not “an officer” and that Section 3 cannot be enforced without related congressional legislation.

Some justices, including Brett Kavanaugh, appeared to agree particularly that Congress, not individual states, should control such disqualification for a national office.

Liberal Justice Elena Kagan separately told Murray, “I think that the question that you have to confront is why a single state should decide who gets to be president of the United States.”

“In other words,” Kagan continued, “this question of whether a former president is disqualified for insurrection to be president again, is, just to say it, it sounds awfully national to me. If you weren’t from Colorado and you were from Wisconsin or you were from Michigan and … what the Michigan secretary of state did is going to make the difference between, you know, whether Candidate A is elected or Candidate B is elected, I mean, that seems quite extraordinary, doesn’t it?”

Calm on the bench as some reporters leave early

Throughout arguments, justices appeared less impatient with each other, and Roberts easily fell into his more administrative role, ensuring justices were able to get all their questions in, preserving some order to issues raised and correcting a misunderstanding in a case reference.

Murray tried but failed to keep the justices’ attention on the January 6 attack and Trump’s actions that first spurred the attempt to remove him from the ballot under the insurrectionist clause.

The justices were not ready to go down that road. The tenor of the arguments indicated that however the justices end up interpreting the 14th Amendment, they will not reach the question of whether Trump engaged in an insurrection, as Colorado judges decreed.

Just as Roberts can set the tone for oral arguments, the chief justice presides over their private votes on cases. In upcoming days, as they take a confidential vote, they will begin negotiating a majority rationale. The court has already set an expedited schedule for the case, and a ruling could come within weeks, rather than the usual months that cases take.

The court sometimes issues rulings with splintered reasoning and multiple concurring opinions. But in this case, an incentive for clarity from the majority exists, to guide states and resolve political confusion. As he strives for consensus, Roberts is likely to try to keep any separate, concurring opinions to a minimum.

Still, the bottom line seemed clear by the time he declared, with the traditional closing, “The case is submitted.”

Even before then, some reporters had abandoned the press section, leaving the rest to take in the air of inevitability.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2024 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.