Stunning video: Rare ‘Octopus Garden’ discovered off California coast

MOSS LANDING, Calif. - Scientists in California and beyond have discovered an "Octopus Garden" of up to 20,000 eight-armed creatures living in the deep sea about 80 miles southwest of Monterey.

Researchers say it's the largest known gathering of octopuses in the world.

In a study published Wednesday in Science Advances, a team of researchers from Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, NOAA’s Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the University of New Hampshire, and the Field Museum released photos, video and scientific facts about this garden, which they have been studying since 2018.

The garden is only one of a handful of known deep-sea octopus nurseries in the world.

MBARI senior scientist Jim Barry, the lead author of the study, said that the reason so many deep-sea octopus congregate in this spot is because there are thermal springs located there. The octopus garden is about two miles below the ocean's surface on a small extinct volcano called Davidson Seamount.

The warmth accelerates the development of octopus eggs, and this shorter brooding period increases a hatchling octopus’ odds for survival. Water in the cracks and crevices of the garden reach about 51 degrees.

Other octopuses that breed in colder waters have a tougher time and often die sooner, the scientists discovered.

"The deep sea is one of the most challenging environments on Earth, yet animals have evolved clever ways to cope with frigid temperatures, perpetual darkness, and extreme pressure. Very long brooding periods increase the likelihood that a mother’s eggs won’t survive. By nesting at hydrothermal springs, octopus moms give their offspring a leg up," Barry said in a news release.

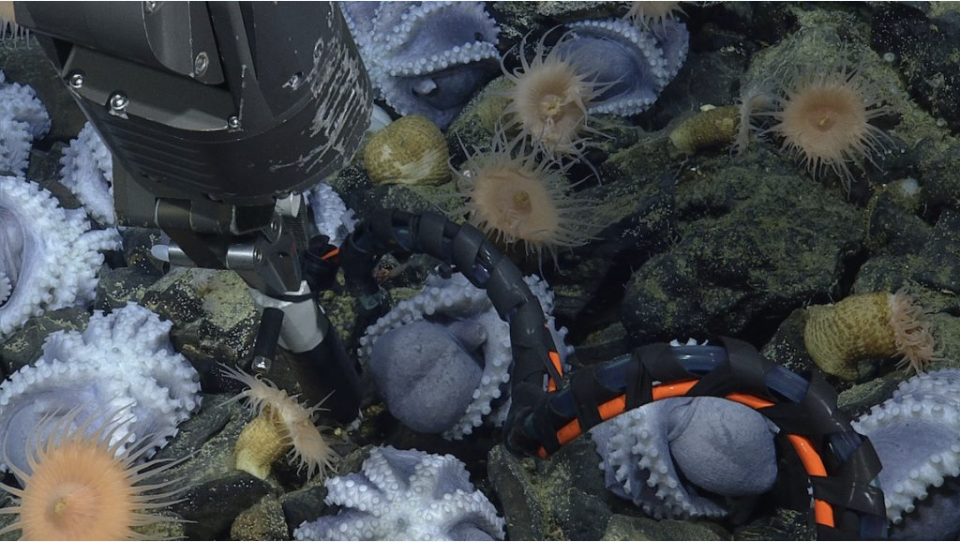

The site is full of Muusoctopus robustus—a species researchers nicknamed the pearl octopus because from a distance, they look like opalescent pearls on the seafloor.

These pearl octopuses meet at this particular site solely to reproduce, the scientists concluded.

Researchers conducted 14 dives over three years to study this phenomenon.

What the scientists also discovered: Like most other cephalopods, pearl octopus die after they reproduce. But as always with the cycle of life, dead octopus provide a feast for scavengers.

The scientists noted that a rich community of invertebrates live alongside the nesting female octopuses, eating the unhatched eggs, vulnerable hatchlings and adult octopus that have died.