AP: Easing fires not as simple as climate change vs. forest work

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) Deadly West Coast wildfires are dividing President Donald Trump and the states’ Democratic leaders over how to prevent blazes from becoming more frequent and destructive, but scientists and others on the front lines say it’s not as simple as blaming either climate change or the way land is managed.

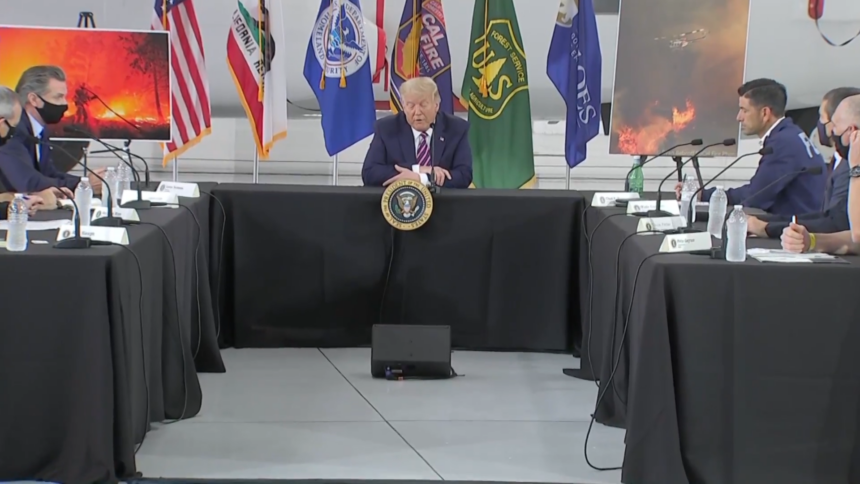

The governors of California, Oregon and Washington have all said global warming is priming forests for wildfires as they become hotter and drier. But during a visit Monday to California a, Trump pointed to how states manage forests and said, “It will start getting cooler, just you watch.”

Scientists say wildfires are all but inevitable, and the main drivers are plants and trees drying out due to climate change and more people living closer to areas that burn. And while forest thinning and controlled burns are solutions, they have proven challenging to implement on the scale needed to combat those threats.

As crews battled wildfires that have killed at least 35 people, destroyed neighborhoods and enveloped the West Coast in smoke, Trump contended that the states are to blame for failing to rake leaves and clear dead timber from forest floors. However, many of the California blazes have roared through coastal chaparral and grasslands, not forest, and some of the largest are burning on federal land.

In Oregon, it was the forests that burned at unprecedented levels this past week. Almost the same number of “megafires” — defined as having scorched 100,000 acres or more — were burning last week as have occurred during the entire last century, said Jim Gersbach, spokesman for the Oregon Department of Forestry.

Experts, environmentalists and loggers largely agree that thinning trees and brush through prescribed burns and careful logging will help prevent forests that cover vast tracts of the American West from threatening cities with fire.

But whether that would have spared towns is less clear. Strong winds sent flames racing down the western slopes of the Cascade Range into small towns like Detroit, Oregon, wiping them out.

“In a wind-driven event at 30 miles an hour, where you’ve got embers flying far ahead of the actual flame fronts and flame lengths being much greater than normal, is thinning going to really be enough to stop a home from burning in an inferno like that?” Gersbach said.

Millions of dollars are spent on tree thinning and brush clearing every year in Western states, though many argue more needs to be done. That costly, labor-intensive work can be undercut when rural homeowners don’t make similar efforts on their own properties.

Forest thinning helped save the town of Sisters, Oregon, from a wildfire in 2017. But scaling the practice up and across a growing area where people live in the mountains and forests of the West has many challenges.

Many places don’t have the capacity or the money to do the work, said John Bailey, an Oregon State University professor of tree growth and fire management. There are no longer enough mills to handle salvageable timber, whose proceeds can help offset the costs of forest thinning.

“Sometimes I feel like we are making progress at increasing the pace and scale of resilience treatments, but largely, the same issues are at play, and progress has been slow,” Bailey said. “More folks are probably ‘on board’ to the ideas, but implementation is hard.”

And as more people move into rural areas of the West or build vacation cabins in the woods, prescribed burning is less of an option.

“Where you have lots of people living on small acreages close together, and you’ve got houses and barns and sheds and corrals and fences, it’s very difficult to do a prescribed burn,” Gersbach said. “You’ve got a lot of things that, if that fire for some reason escapes, you’re almost immediately into someone else’s property.”

The West Coast governors have bluntly laid the blame on climate change and accused the Trump administration of downplaying the threat, with Washington Gov. Jay Inslee calling it “a blowtorch over our states in the West.”

California Gov. Gavin Newsom has called out the “ideological BS” of those who deny the danger and noted that California had its hottest August on record. The state had 14,000 dry lightning strikes that set off hundreds of fires, some that combined into creating five of the 10 largest fires in the state’s recorded history.

Oregon Gov. Kate Brown said about 500,000 acres typically burn each year, but just in the past week, flames have swallowed over a million acres, pointing to long-term drought and recent wild weather swings in the state.

“This is truly the bellwether for climate change on the West Coast,” she said Sunday on CBS’ “Face the Nation.”

It isn’t clear if global warming caused the dry, windy conditions that have fed the fires in the Pacific Northwest, but a warmer world can increase the likelihood of extreme events and contribute to their severity, said Greg Jones, a professor and research climatologist at Linfield University in McMinnville, Oregon.

In southern Oregon to Northern California, warnings of low moisture and strong winds, conditions that can drive the flames, are in effect through Tuesday. Tens of thousands of people have fled their homes as the fast-moving flames turned neighborhoods to nothing but charred rubble and burned-out cars.

At least 10 people have been killed in Oregon. Officials more than 20 people are still missing, and the number of fatalities is likely to rise as authorities search. In California, 24 people have died, and one person was killed in Washington state.