How and why American workers disengaged from their jobs in 2022

fizkes // Shutterstock

How and why American workers disengaged from their jobs in 2022

Worker with sticky notes covering eyes.

Wake up. Clock in for work. Survive. Clock out. Check the news. Sleep. Wake up. Clock in. Survive. Check the news. Repeat.

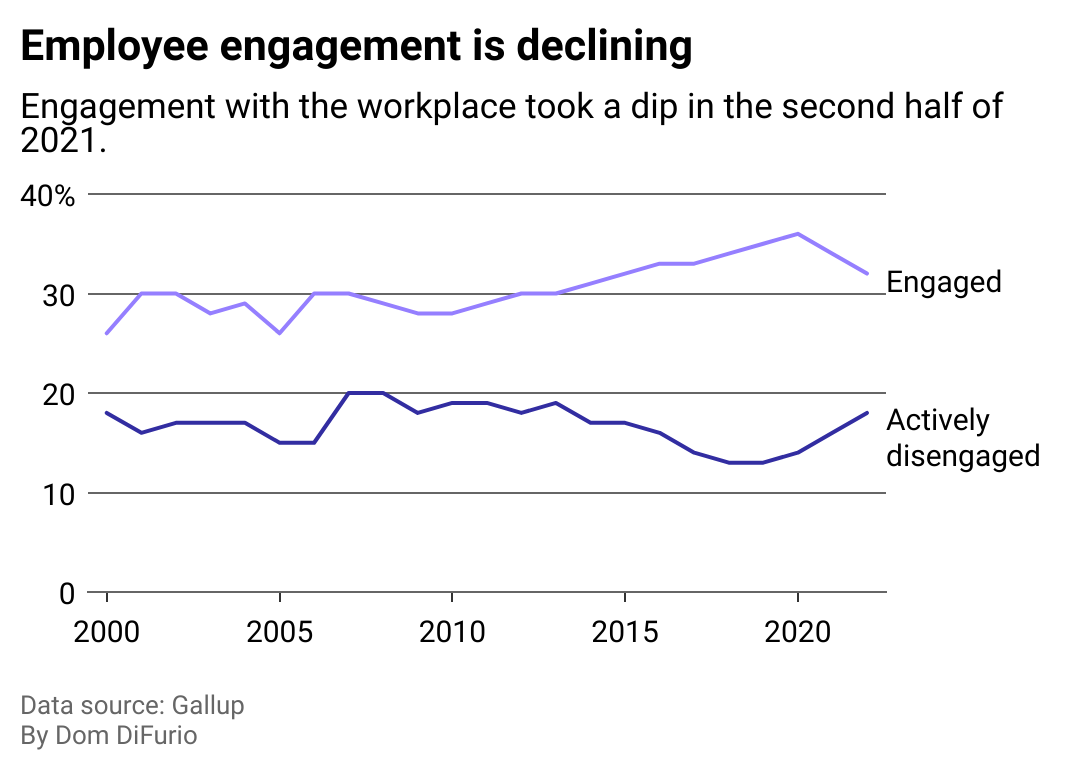

For roughly two years, many Americans lived an abnormally restrained life amid a raging global pandemic the likes of which the modern working world had never experienced. The effects of the massive disruption to our nation are still being felt in workplaces everywhere: More workers reported being disengaged at work in 2022 than any time in at least the previous decade.

It’s a trend that has yet to let up, according to Gallup polling. Just 1 in 3 workers reported they were engaged at work in 2022. Those are the employees who feel enthusiastic about their job. The remaining 2 in 3 are either generally disengaged or—more significantly—”actively disengaged,” feeling disgruntled and disloyal “because most of their workplace needs are unmet,” as Gallup reports.

Sana analyzed public polls and data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to determine how Americans are distancing themselves emotionally from work and how that compares to recent history.

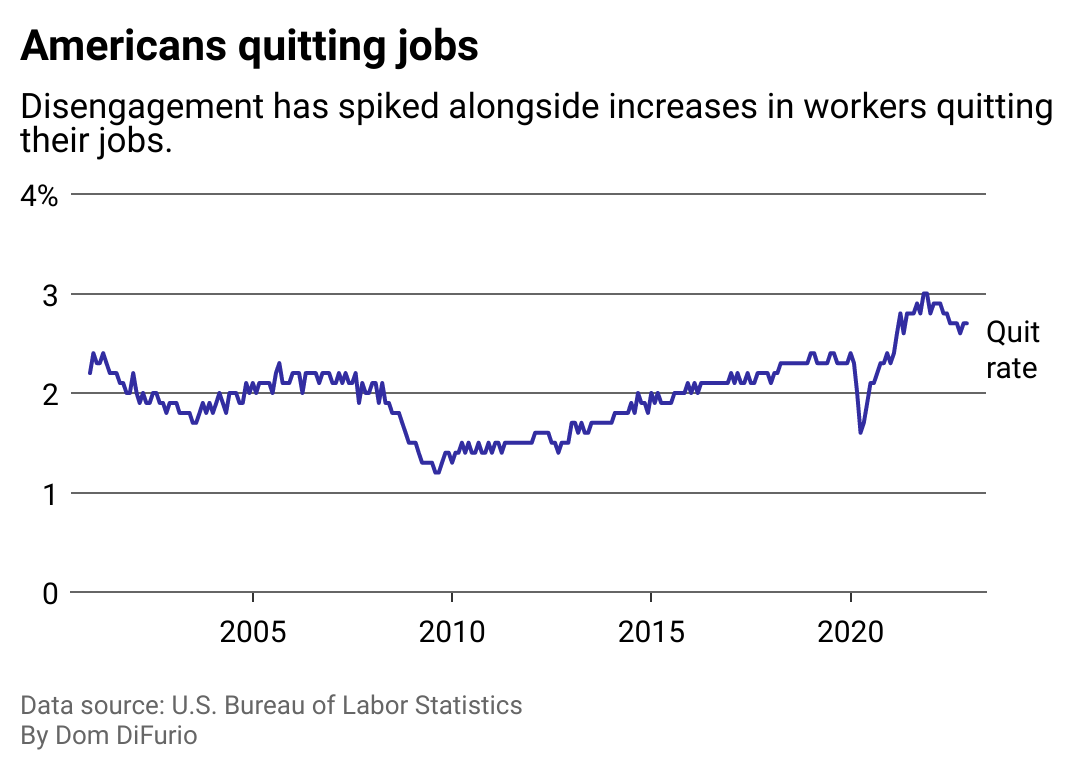

Starting in 2021 and coinciding with the rollout of vaccines, American workers began quitting in droves in a move dubbed “The Great Resignation.” Polling from Pew Research Center reveals that most of these workers sought higher pay and more opportunities for advancement.

But many who stayed in their jobs also started checking out of work psychologically or disengaging. Some of the signs of disengaged employees include withdrawing from teams, missing deadlines for everyday work and tasks, and a lack of communication with coworkers or their managers. That change in sentiment can be widespread, showing up in the rank-and-file as well as in management, according to Gallup.

![]()

Sana

Employees checked out after 2020

A chart showing a line for employees who say they’re engaged at work, which began declining in 2021 and a line showing actively disengaged employees trending up and to the right over the same time period.

Rice University dean of academic affairs and professor of management and psychology Jing Zhou is among the most-cited academics studying organizational behavior. Zhou believes widespread trauma from living and working through years of a global-scale crisis can’t be ruled out as one lingering factor in the disengagement seen today.

“After that, I think some people are going to … almost kind of hide for a while,” Zhou said. “Psychologically they just don’t want to engage in any uncertainty or challenge anymore.”

If workers weren’t hobbled by long-term illness themselves in recent years, they likely knew someone who was, or else cared for someone suffering from the long-term effects of COVID-19. By the summer of 2022, roughly 1 in 3 working-age American adults reported they were dealing with long-term COVID-19 symptoms lasting three months or more, according to weekly surveys conducted by the Census Bureau.

And the working parents receiving emails from employers who wanted them back in physical offices in 2022 had an estimated 10,000 fewer options for child care nationwide, according to the nonprofit advocacy group Child Care Aware of America. Those services, some provided by small businesses run out of people’s homes, were forced to close for safety as the pandemic hit. Many never reopened: 100,000 child care workers fled for jobs with better working conditions, including higher pay.

Even those who could find child care and whose loved ones dodged the worst outcomes of COVID-19 showed up every day to workplaces where absenteeism was unusually high due to the spreading disease—and where those who did arrive were often asked to pick up the slack.

In 2022, 3.6% of the workforce reported having missed work, up from 2.8% in 2019—the last full working year before COVID-19 arrived. That figure represents time off due to illness, medical issues, injury, child care problems, or other family or personal obligations. It does not reflect personal days, holiday time off, or work not done because of labor disputes.

Sana

Drop in engagement comes as workers quit in droves

A chart showing a line representing the percentage of workers quitting their jobs each month, which peaks in 2021 before falling slightly in 2022.

Initial reports of this shift in the workforce earned the phenomenon a catchy name in media circles that some have suggested is a loaded term implying workers are opportunistic or lazy— “quiet quitting.”

Some have pointed to a TikTok video posted by career coach Bryan Creely in early 2022 as the origin of the term.

“Let’s face it, companies are very desperate right now to hire people,” Creely told viewers. “This obviously wouldn’t be a long-term strategy or a strategy for those of you who care about climbing up the corporate ladder, but for those of you who don’t and you’re feeling burned out, maybe dial it back a little bit because you won’t be the only one.”

Those disengaged workers the coach speaks of are more likely to be under 35, female, and working in-person performing a job that could be performed remotely, according to Gallup polling.

Zhou interprets the disengagement not as taking advantage or being lazy, but as a “cry for help.”

“Fundamentally, psychological engagement is a kind of psychological ownership,” Zhou said. “If I have a sense of ownership in this workplace, I will be engaged because I feel like I am a part of this. I own this. I have a say … and I’m responsible for my success and our success.”

Whether or not this cry for help is recognized from organization to organization may depend on a crop of executives trained in the late 20th century in what Zhou described as a “command and control” style of management.

Numerous studies show workers spent some of the last few years reexamining the value of work in their lives since the pandemic’s arrival. A late 2021 survey from advisory firm Gartner found 52% of respondents questioned the purpose of their day-to-day job. The firm’s chief researcher warned employers may suffer if they sit back and assume workers will get through this rut by themselves. Throughout 2022 the labor market remained in workers’ favor with nearly two job openings for every unemployed person seeking work.

fizkes // Shutterstock

Wanted: Engaged managers and clear expectations

Woman working at desktop computer in office.

The solution for employers, Zhou suggested, lies not in self-care exhortations, productivity pep talks, or mental health webinars, but in helping workers feel ownership over their jobs.

Pay is one piece of how workers find value and ownership in their work, but Zhou warns pay alone isn’t enough. Workers must also feel they have meaning each day they show up to work. And that starts with strong managers.

“I’m hoping more and more companies will see the need to retrain their managers in terms of how to use intrinsic motivators to engage their employees,” Zhou said.

Polling from last year indicates some ways employers can begin to dig into the ownership conundrum. In 2022, fewer workers felt their opinions mattered at work than reported feeling that way pre-pandemic in 2019. Fewer workers also reported feeling they had opportunities to grow, their work expectations were clear, and they had a connection to the mission of their organization.

But Zhou is optimistic. “Just by talking about disengagement, we are making progress,” she said.

This story originally appeared on Sana and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.