Online creators hit with IP and copyright lawsuits

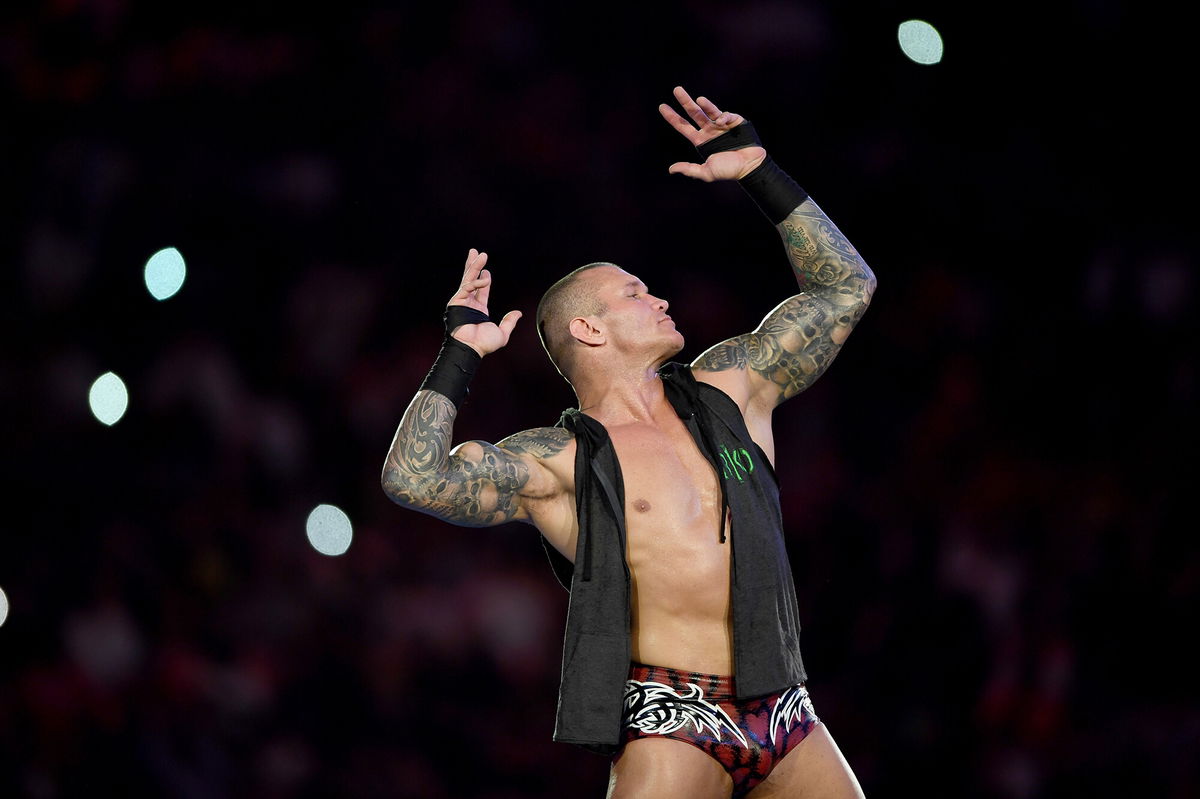

World Heavyweight Champion Randy Orton poses for photographers during the World Wrestling Entertainment Super Showdown event in the Saudi Red Sea port city of Jeddah late on January 7

By Alexandra Peers/ CNN Business

It’s weird when wrestling superstar Randy Orton, Netflix’s romance “Bridgerton,” TikTok, a tattoo artist, Instagram, NFTs and Andy Warhol’s portrait of Prince all show up in the same law school textbook.

A series of hot-button lawsuits have linked all those unlikely creators and platforms in litigation that goes as high as the US Supreme Court. The litigation deals with issues of intellectual property, copyright infringement and fair use in a rapidly changing new-media landscape.

For decades, so-called “copycat” lawsuits boiled down to ‘you stole my song/book/idea.’ Now, as the number of platforms to showcase artistic content have multiplied, these court cases are testing the rights of fans, creators and rivals to reinterpret other people’s intellectual property.

At issue, particularly in social media or new technology, is exactly how much you have to transform something to profit and get credit for it, literally, to make it your business.

Three weeks ago, in a first-of-its-kind case, a jury in an Illinois federal court ruled that tattoo artist Catherine Alexander’s copyright was violated when the likeness of her client, World Wrestling Entertainment star Randy Orton, was depicted in a video game. Alexander has tattooed Orton’s arms from his shoulders to his wrists.

She won, but not much: $3,750, because the court ruled that, though her copyright had been violated, her tattoos didn’t impact game profits. Nonetheless, it set a precedent.

The ruling calls into question the abilities of people with tattoos “to control the right to make or license realistic depictions of their own likenesses,” said Aaron J. Moss, a Hollywood litigation attorney specializing in copyright matters.

Blame the rise of remix culture. For most of the twentieth century, mass content was created and distributed by professionals,” said Moss. “Individuals were consumers. Legal issues were pretty straightforward. But, now, most of the time, the content is being repurposed, remixed or repackaged.”

“It’s all new and it’s all a mess,” said Victor Wiener, a fine-art appraiser who’s consulted for Lloyd’s of London and serves as an expert witness in art-valuation court cases. Over the past several decades, the distinctions between professionals and amateurs, artists and copycats and between production and consumption have blurred. In such gray areas, said Wiener, “it can come down to who the judge, or the tryer of fact, believes.”

Streaming service Netflix late last month settled a copyright lawsuit against fans of their Regency romance “Bridgerton” who wrote and workshopped an “Unofficial Bridgerton Musical” on TikTok.

In January 2021, a month after the Netflix show premiered, singer Abigail Barlow teamed up with musician Emily Bear to create their own interpretation of the hit series. In a souped-up version of fan fiction, the two women began to write and to perform songs they had written, often using exact dialogue from the series.

It was a huge hit on TikTok, in part because the duo invited feedback and participation, making it a crowd-sourced artwork.

At first Netflix applauded the effort and even okayed the recording of an album of songs. But when the creators took their show on the road and sold tickets, Netflix sued.

Producer and series creator Shondra Rhimes, in a statement released when the suit was filed in July, said “what started as a fun celebration by [fans] on social media has turned into the blatant taking of intellectual property.”

Cases like this turn on “fair use,” matters such as how much of another work someone appropriates. Or whether it dents the original creator’s ability to profit. In the case of “Bridgerton,” neither side has commented on the resolution of the suit, but a planned performance of the musical at Royal Albert Hall scheduled for last month was cancelled.

Uncontrolled misappropriation is particularly common in the relatively new NFT art field.

“Today, a 15-year-old can copy your work and spread it across the Internet like feral cat pee at no cost and with little effort. The intellectual capital of an artist can be appropriated on a massive, global scale unimaginable by the people who wrote copyright laws,” said John Wolpert, co-founder of the IBM blockchain and of several blockchain projects.

And the relatively new phenomenon of trading art NFTs with cryptocurrency “has created a perverse new incentive to misappropriate an artist’s work and to claim it as your own and charge people to purchase it,” he added.

In one of several NFT suits finding their way to the courts, fashion giant Hermes sued L.A. artist Mason Rothschild after he created 100 NFT’s that depicted Hermes Birkin bags wrapped in fake fur.

Hermes filed a lawsuit in January in the court of the Southern District in New York charging trademark infringement and injury to business reputation, not to mention “rip off,” with Hermes requesting a quick summary judgment.

But in the past, courts have often bent over backward to give an artist leeway in critique and parody. Rebecca Tushnet, a Harvard Law professor and expert on copyright and trademark law who represents the artist, has argued his “MetaBirkins” art project is essentially protected as it comments on the relationship between consumerism and the value of art.

Last month, the Central District court of California ruled on a doozy of a copyright lawsuit that arose via Instagram: Carlos Vila v. Deadly Doll.

In 2020, the photographer had taken an image of model Irina Shayk. She was wearing sweatpants from fashion company Deadly Doll that featured a large illustration of a woman carrying a skull. The photographer subsequently licensed his image of the model for reproduction. Deadly Doll posted Vila’s photo on their Instagram account and he sued. They counter-sued, arguing he was the infringer. The suit, detailed by litigator Moss in his Copyright Lately blog, is moving forward in California.

Perhaps the most important case has nothing to do with new media — it concerns Andy Warhol’s altered photograph of the late artist Prince that ran in Vanity Fair magazine years ago. But it is expected to set a precedent.

Right now, the US Supreme Court is hearing this landmark case regarding Warhol’s alleged misappropriation of photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s work in his silkscreens of Prince. The court is set to determine how, and how much, an artist or creator must transform a work to make it their own — guidelines that will surely create as much of a buzz as the intellectual property itself.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2022 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.