Julia Ducournau explains the crippling love beneath her beautiful dark twisted fantasy ‘Titane’

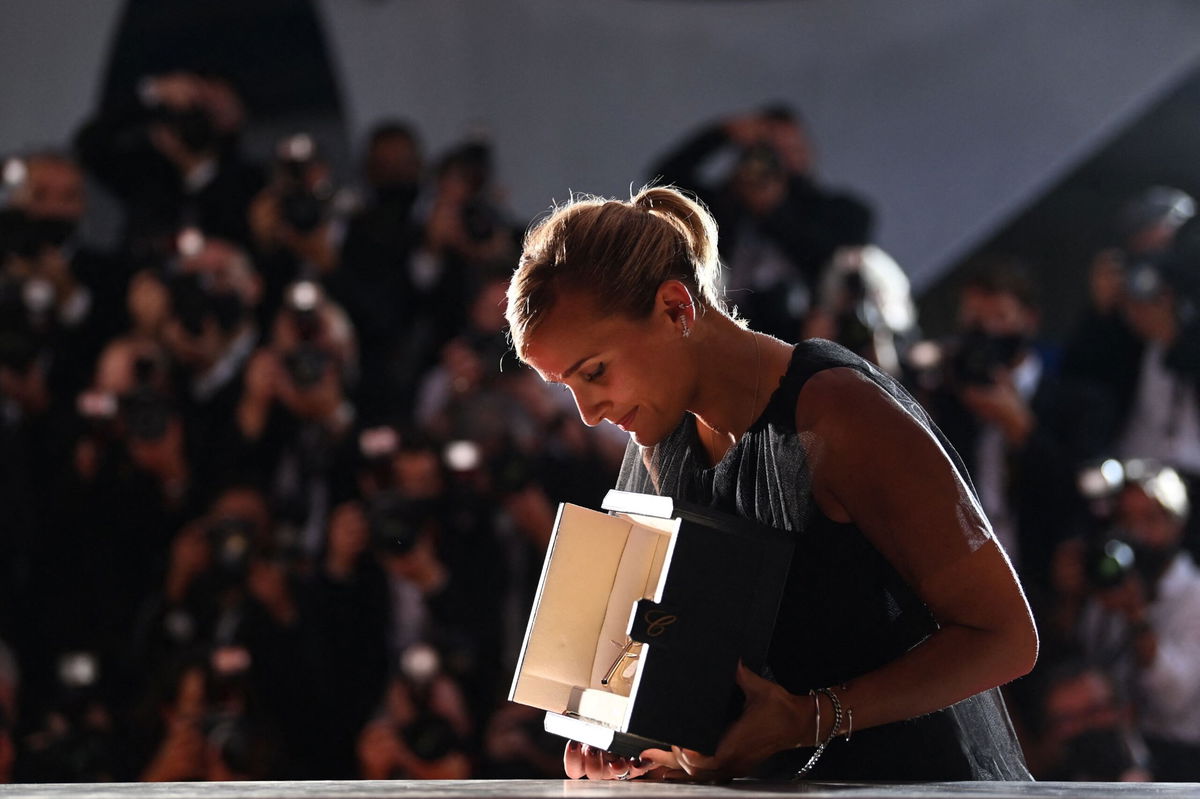

French director Julia Ducournau looks at her Palme d'Or for "Titane" at the closing ceremony of the 74th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in Cannes

Thomas Page, CNN

Julia Ducournau lights a cigarette, as if to punctuate her point. The French writer-director had been musing about love in her film “Titane,” a through line buried beneath much hysteria since it won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year. Love, she insisted, is the foundation of the whole movie — though it’s intractable.

“It’s quite hard to talk about,” Ducournau said via video call. “It’s something that a lot of people seem to handle so well in films, in series, in art in general. For me, I felt a bit crippled by the topic.”

It’s a surprising admission from a filmmaker whose every on-screen move is delivered with total conviction. In her debut film “Raw,” burgeoning cannibal Justine tears at her sister’s severed finger like a chicken wing. In her follow-up, “Titane,” protagonist Alexia bucks in the throes of ecstasy courtesy of an amorous muscle car (giving new meaning to the term “autoerotic” in the process). The thought of Ducournau at an impasse of any kind would be amusing if she wasn’t being so sincere.

“Titane” centers on Alexia (Agathe Rousselle), the survivor of a childhood car crash who has since become a dancer at auto shows. Objectified, sexualized and sporting a scar from the insertion of a metal plate into her skull, Alexia has a thing for cars themselves. One night she does the deed with a Cadillac, only to become pregnant. She’s also a serial killer, and when a bout of bloody mayhem goes awry, Alexia is forced into hiding, posing as Adrien, the long-lost son of firefighter and steroid junkie Vincent (Vincent Lindon). Despite attempts to conceal her body from Vincent, her baby bump continues growing at an alarming rate. She can only keep the truth inside for so long.

Ducournau picks up genre tropes, plays with them, subverts them and then tosses them away before they outstay their welcome. In its most skeletal form, the plot reads as a provocation, even if the meat of the film is quite different. Has the sensationalizing of “Titane” been unhelpful? “Unhelpful? I don’t know,” she wondered, before pausing. “I think it’s unavoidable.”

“I can’t dictate what people are going to think of my film or which scenes they’re going to remember,” she added. “At some point I show you my film and you make it your own. Your reaction says more about yourself than about the film.”

Letting go must be hard. “It’s an effort, for sure,” Ducournau said. “We’re doing an interview right now. But the truth is that I’ve said it all in my film. I can’t say it better than I did in my film.”

“Titane,” she said, was an exploration of why she felt so immobilized by love. To do so, she reached for the absolute, the unconditional; the kind of love that you need to see being born, because how else could you possibly believe it exists? The means by which she arrives at the nub of her story has proved controversial to some. But if you only read the more churlish headlines about “Titane,” you may have missed the tender heart beating beneath the blood, oil and chrome.

Ducournau says she was inspired by the ancient Greek creation myth of Uranus (heaven) and Gaea (Earth), whose union produced a pantheon of 12 gods, known as the Titans and Titanides, and a “new humanity that is quite monstrous.” (“Titane” is French for both titanium and the female form of Titan.) In the myths, the family dynamics are complex, rife with violence and rebellion, and play out in muscular, elemental terms not unlike Ducournau’s own filmmaking.

The director speaks of “trying to build an umbilical cord between you and the character … for me, bodies are essential for that.” Alexia stabs, scratches and punches her way through life, doing as much harm to herself as others. But where she truly asserts her autonomy, more so than murder, is through music and dance. She’s near mute, but we understand Alexia because we feel everything, including her emotional awakening.

“I knew this was not going to be the place for words. I was afraid words were going to belittle it; that it was going to somehow try and restrain it,” the director explained.

Uranus, who was both the son and consort of Gaea, is not the only product of immaculate conception cited by the director. The Bible looms large in Ducournau’s film, and it is served with a dose of gender fluidity. We see a young Alexia, post-surgery, wearing a metal halo (or a crown of thorns, explained the director), palms aloft as if to show her father the stigmata. Vincent, a self-proclaimed god among firefighters, introduces Alexia (then Adrien) to his team as Jesus. Then there’s the pregnancy.

“Throughout the film, what I have built up is (Alexia) going from Jesus to Mary to Jesus to Mary and to Jesus again,” Ducournau explained. “At the end, for me, she becomes both. It’s almost like Jesus-Mary giving birth to Jesus-Mary.” (Though the child, she said, is female.)

“I don’t perceive (the Biblical references) as being religious,” she insisted. “I do like to chase the sacred … but this sacred is the sacred of humanity. It’s more about all the possibilities of humanity, in terms of transformation.”

Does Vincent ever really believe Alexia is his long-lost son? It’s perhaps the wrong way to look at it. Caring for her is an act of faith and submission, his unconditional love finding a new host. It’s an arc that sees Alexia, a murderous psychopath who Ducournau “can’t relate to,” become Adrien, broken and afraid but capable of feeling.

“Love is capable of making you see someone for who they are, no matter what social constructs you could have put on them, no matter what representation or expectations you had for them,” the director said.

By the denouement, both characters have professed their love for each other. “You know, the ‘I love you’ at the end,” she said, “I wrote it, then I unwrote it and I wrote it again, unwrote it. I was like, ‘This f**king line is really bothering me!’ We understand that they love each other, do I need the word? Then I saw the word as a big stepping stone. It’s really something that we need in order to pass the last threshold, somehow, towards humanity.”

Ultimately, words didn’t belittle the act, after all.

In July, the French director became only the second woman to be awarded the Palme d’Or, the Cannes Film Festival’s top prize (Jane Campion was the first, for “The Piano” in 1993). It was a shock win, and not just because Spike Lee announced the victory by accident at the start of the ceremony. For every critic calling it “bizarrely beautiful” there was another decrying its “towering pointlessness.”

Polarized reactions at festival screenings have since given way to more considered debate upon the movie’s general release. Even so, France’s decision to submit “Titane” as its official entry for the Academy Awards was something of a surprise.

“I did not expect it,” said Ducournau. “In spite of the Palme d’Or, I thought that maybe my film was too controversial … it doesn’t represent traditional French submissions.”

What does it say about the state of the nation’s film industry? “I think it says quite a lot about how genre is going to be considered in France, maybe, from now on,” Ducournau said. “I don’t think it’s going to be a black and white thing, but I think it means that France is actually starting to give credit to genre filmmakers as being serious authors as well — and you know how important the concept of being an author is in France.”

Does this stand her in good stead going forward? Where else would she like to explore?

“I know what I’m going to explore next, but I can’t talk about it,” she teased, laughing. “But love, love, love, again. Always love.”

Top image: Julia Ducournau directs Agathe Rouselle in a scene in “Titane.”

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2021 Cable News Network, Inc., a WarnerMedia Company. All rights reserved.