Q&A: The head of the FDA answers why parents are still struggling to find baby formula and when things might return to normal

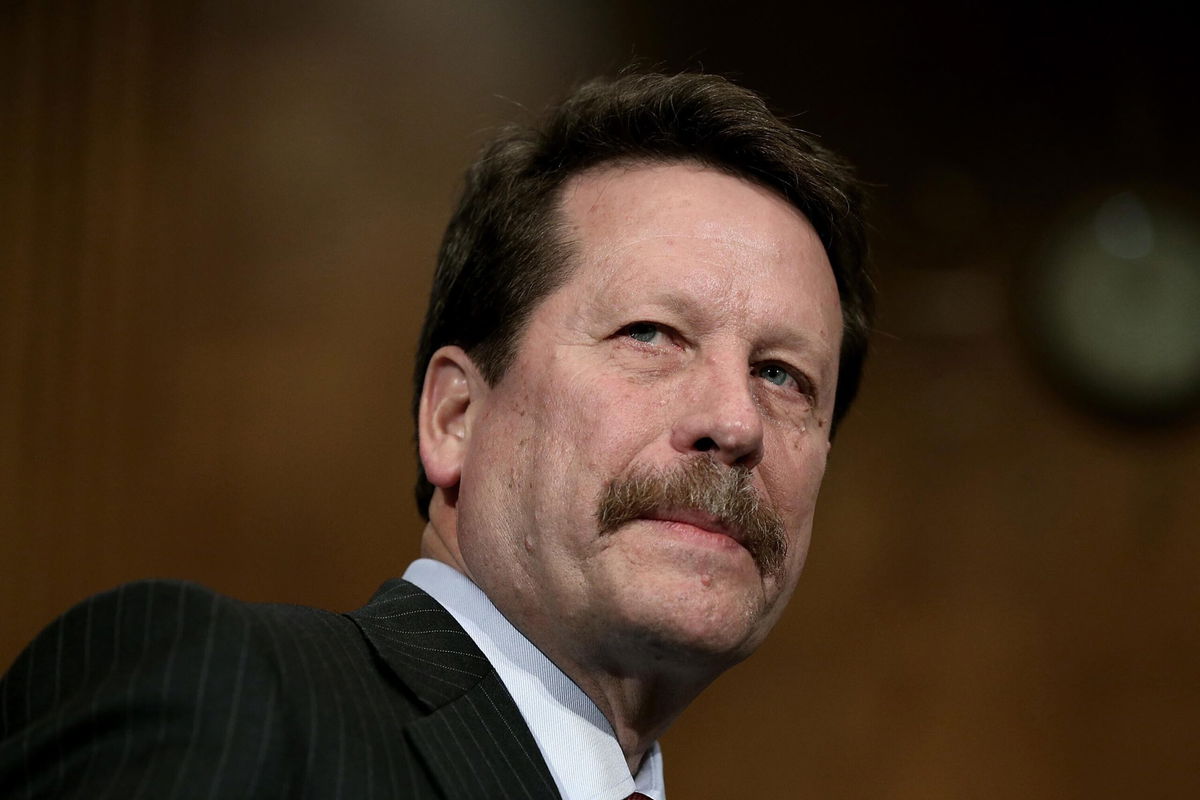

Dr. Robert Califf

By MJ Lee, CNN White House correspondent

Dr. Robert Califf, a cardiologist by training, admits that he never imagined he would one day become an expert on infant formula.

But during the eight months Califf has served as head of the US Food and Drug Administration under President Joe Biden, baby formula emerged as one of the most urgent and time-consuming issues for the commissioner, after major recalls of formula produced at an Abbott plant in Michigan spurred a full-blown national shortage.

While Biden administration officials have been scrambling to remedy the scarcity of infant formula for the better part of this year — doing everything from flying in crates full of formula from abroad to invoking the Defense Production Act to boost production — the shortage still isn’t over heading into the winter months.

Some parents — nearly a third of households with a baby younger than one — said they struggled to find formula over the course of one week last month, while more than 4 in 10 households said they only had a week’s supply or less of baby food on hand. Those data points come from a recent US Census Bureau survey, which has some limitations including a limited sample size and no previous points of comparison on the baby formula issue.

In a lengthy interview with CNN this week, Califf predicted that the US was now “a couple of months” away from the situation normalizing to pre-recall levels and insisted that, despite ongoing reports of gaps on shelves and anxious parents, formula production was now consistently outpacing consumption.

At the same time, Califf wouldn’t rule out the possibility of the US needing to launch another “Operation Fly Formula” flight from overseas — “If something else happened that was unexpected, like a plant shutting down or some other phenomenon like that,” he said. The last flight, on September 29, delivered more than 100,000 pounds of Nestle formula from the Netherlands to the US.

The commissioner shared that at the peak of the formula crisis, he had more than one “very tense” conversation with the head of Abbott — the company that makes popular formula labels like Similac and specialty formulas such as EleCare.

Califf also said he has not spoken directly with Biden about the infant formula issue — “I’ve talked a lot with Ron Klain,” Califf said of the President’s chief of staff — and that while he has not visited the Abbott plant in Sturgis, Michigan, behind the recalls, he hopes to do that soon.

Senior administration officials who have been intimately involved in addressing the baby formula shortage told CNN that a key issue they are currently monitoring is a “variety problem” — where at any given moment, store shelves might carry a lot of some products, but none of others.

The single biggest factor causing this imbalance? “The root cause of everything is the fact that Sturgis had to shut down, and Sturgis is still not fully back online,” one official said recently.

“How do we prevent this from happening again?”

While administration officials are starting to feel increasingly better about the availability of baby formula in the US, with production levels so far this year outpacing 2021 levels, the shortage invited a barrage of criticism and questions about what other important commodities could be vulnerable to similarly grave supply disruptions.

In interviews with CNN, officials pointed to the infant formula crisis as having prompted a kind of reckoning — and admittedly a much-needed one — for the government to put better systems in place to analyze the nation’s supply chains and pinpoint, ahead of time, the areas of real vulnerabilities.

This inter-agency work is still in the early stages, but officials insist that the federal government is already better equipped to tackle supply chain disruptions, and that there is coordination, data-sharing and analysis among the various agencies that simply didn’t exist before.

One food product that officials point to as an example is meat, because the meat processing industry is highly concentrated. Another example is sunflower oil: Ukraine was the largest exporter of it before the war.

“I’d say every commodity we regulate pretty much has a risk at this point, because as we look at the future of foods, climate change, international strife — the fact that the industries have gone to ‘just in time’ distribution systems, which keep a low inventory to reduce costs, creates a system which is vulnerable,” Califf said.

On the baby formula crisis, and what message he would want to deliver to concerned parents and caregivers, Califf said: “I’m a grandfather and I have grandchildren and I’ve had children myself. We at the FDA are very aware of the difficulty this has caused for families and we want them to know that we’re working hard until we get things back to normal and will continue to work hard to deal with it, every single day.”

Q-and-A

CNN: Why do you think in the month of October, parents and families are still having trouble finding baby formula? Why is it that the US is still having to fly in formula from abroad?

Califf: Well, I mean, first of all, I would just say that it has taken time obviously to not only fill the shelves, but we’ve got this other issue — something that I never thought I would be an expert in — called SKU consolidation. And while we’re confident that the amount of formula being produced is greater than the amount consumed for quite a number of weeks and many of the retailers have a supply in the intermediate distribution chains, the producers are not making all the different types and sizes of formula that they made before the shortage because what they do is consolidate their production, as I think you know, they’ve been working three shifts seven days a week. … There’s still going to be empty spots on the shelves because all the different types and sizes of the formula are not being produced and distributed.

… There are going to be distribution inefficiencies, I guess you call them, where some places may not get the supply that they were used to getting in the past. So, I think there’s really good evidence that it’s getting better, but we’re not all the way there yet. It’s going take a bit more time for the reasons that I just gave.

CNN: Is there an estimated timeline for when you think the baby formula situation will basically return to normal? Are we talking about a couple more weeks, a couple more months, by the end of the year?

Califf: Timeframes are treacherous, you know that. First of all, I’d say we have to describe what normal is. If you’re talking about pre-pandemic normal, I think that’s very unpredictable. If you’re talking about post-pandemic, pre-Abbott recall normal, I’d say we’re in the months, you know, a couple of months timeframe. Because, as I said, the production is outstripping the demand by quite a bit at this point. So, it’s just a matter of filling up all those intermediate distribution points.

A really important factor: This is when I was not in the job yet but early — I still vividly remember early in the pandemic — how there were all those empty shelves just about everywhere and infant formula never got back to the pre-pandemic state. But definitely, you know, with the Abbott recall, things changed very dramatically, as you documented quite vividly on CNN. So, I think our goal right now is to get back … to the post-pandemic normal, which, and then we have to work on all the supply chains on just about everything that we regulate.

CNN: Administration officials I’ve spoken to basically said there’s not a set timeline for when, specifically, the flights — Operation Fly Formula — are going to end. They may not necessarily have something scheduled right now, but that the door is remaining open in case they need something. Do you have any sort of prediction as to how long you think the US will need to continue bringing in formula from abroad?

Califf: I don’t think we’re using flights right this moment. And it would only be if something else happened that was unexpected, like a plant shutting down or some other phenomenon like that, that we would need it. Because remember, we tend to talk about domestic and foreign but the companies — the two companies that really have had this enormous market share in the US — are global companies. Abbott is a global company and Rickett is actually headquartered in the UK. So, all the different people that are now bringing formula in who weren’t before are developing their own normal routes of distribution without the need for government assistance. So, we don’t think that’s going to be needed unless something unexpected happens.

CNN: What exactly is happening right now with the Abbott plant in Sturgis? Some of the senior officials I’ve spoken to recently — they point to the fact that, one, the plant shut down, and two, it is still not fully back online. And they say that Abbott is the single root cause for some of the ongoing issues.

Califf: Well, I’d say the Abbott plant is a very old plant. It’s been there for a long time. And there were multiple problems and then we had that flood, which was like a once-in-a-hundred-year event, you can’t — it’s hard to imagine you would have such bad luck. And that, you know, causes even more problems and you know, I would say right now the Abbott plant is pretty much fully back online, but they are in a normal period of maintenance every year.

Again, I was not an expert on infant formula, but I feel like I’ve become one now. Every year around early fall, it’s been the norm in the industry to shut down for a couple of weeks to do all the maintenance and repair that you need. And when that happens, you know they’re probably in an old plant like that, they’re likely to discover some things that they want to tidy up but right now Abbott is exceeding their prior production that they had in years past by making it up in other facilities, so we’re still producing a lot of formula. The plan right now is to get a predicted projected maintenance phase.

CNN: Why did they need a separate maintenance phase? All year, going back to February, they were presumably doing maintenance, right? They are trying to get the plant back up and running. The flood happened, as you mentioned.

Califf: I just think, you know, it’s very hard to look at things while you’re working three shifts a day, seven days a week. You’re really need to sort of look at everything functioning. I just think it’s the norm for the maintenance of facilities. I must say I’m not an industrial production expert. But one thing that happened, which I think is really important, we now have a system where all of the companies are sending us their projections on what they’re going to produce. And we’re also able to track what people are buying. I’ll point out to you that this is voluntary. We’ve tried to get congressional authority to get supply chain data as a routine and we’ve been unsuccessful so far. But we are able to track — not only track but also predict — the companies, you know, since we got started on this are pretty much right on target. So yeah, it’s a reason … that we’re as confident as we can be that things are on track.

CNN: Have you been to that plant?

Califf: I have not, but I’m looking forward to going. I want to — hope to make a visit with Congressman Upton and maybe others who are in the Michigan delegation. But I’ve been on numerous calls with the leadership as we worked through this.

CNN: Can you give us a sense of what your communication with folks at Abbott has been like going back to February? Were those conversations ever heated? Did you ever just say — we’re ticked off over here and this is really problematic and you better fix it?

Califf: Well, I think it’s fair to say that things were very tense in the initial conversations. We had that period before we reached agreement on the consent decree. It took a while to reach that agreement and, you know, once we realized the extent of the status of the plan, we were insistent that it get fixed and, in fact, insistent that we needed a consent decree, which essentially gives us joint responsibility for the functioning of the plant. So, it was definitely tense until we reached a consent decree. But once you got past that step, I would say that discussions have been professional. They have a very deep knowledge of the degree of consternation.

You know, many of our people have been working seven days a week — many, many calls on nights and weekends. And we’re doing this on top of the normal work the FDA has to do in the midst of a pandemic. So, they’re aware of how much stress is put on us, but I will say since the consent decree, it’s been very professional. They have followed through on what they said they were going to do. When problems have occurred, and there have been some, they’ve let us know so that we can work on them together. And we have people essentially, either physically or virtually in the plant every day.

CNN: You mean FDA officials?

Califf: Yeah. Either there physically or on regular calls that occur between FDA and Abbott about things that they’re working on.

CNN: When you spoke with Abbott, especially at the height of the crisis, was that with the head of Abbott directly?

Califf: The head of Abbott, yeah. We’ve had multiple calls, I would say, and very direct. When issues are seen on either side, we’ve called each other to try to minimize any misperceptions that might occur about what needs to be done.

CNN: How is all of this affecting people right now who use WIC to get baby formula? Is it fair to say that given the different state-by-state policies, there are people in certain places who are feeling the crisis more?

Califf: Obviously, the WIC program is very important to the entire United States. Over half of infant formula goes through the WIC program and these massive contracts that are given state by state. So, the ones that were Abbott states obviously were directly impacted and WIC had to scramble, and the states had to scramble to provide alternatives for families, and that definitely caused some problems. But even the states that weren’t Abbott contracts, because all the other manufacturers were scrambling to make up for the total deficit, also experienced hardship. And I feel like in the United States, when things go badly, it’s always the people that were in the lowest income have the hardest time and that’s true in our health care system, and I think it was true — we are very sensitive to it and try to, continue to try to do what we can to make up for it. But there’s no question that this is the hardest on the people in the lowest part of our income.

CNN: What is it that WIC program participants are dealing with right now? Are the lowest income families having the hardest time?

Califf: Well, first of all, I’d say the people who run the WIC program, they’ve worked really hard. To my knowledge, everyone can get infant formula. But there’s no doubt that a number of individuals and families have had to make efforts and spend time that they otherwise would not have had to do in order to get it. There was a quote in The Atlantic by one of your reporter colleagues that got my attention a couple of weeks ago, which I think describes the problem in America, related to the pandemic but it’s a similar issue. The quote was that “technological solution walks into the penthouses of America, and diseases seep into the cracks in America.” And I think you know, those with more wealth and more means are more able to do what it takes to find the formula they need. It’s harder on people who have more stressed circumstances.

CNN: Baby formula aside — what are the food items that have been identified by your agency as potentially vulnerable to this kind of supply chain disruption that we’ve seen with baby formula, where one plant shutting down or one company having a serious issue could lead to this kind of nationwide shortage?

Califf: I’d say every commodity we regulate pretty much has a risk at this point, because as we look at the future of foods, climate change, international strife — the fact that the industries have gone to ‘just in time’ distribution systems, which keep a low inventory to reduce costs, creates a system which is vulnerable.

Don’t forget that we also have drug shortages and we have a shortage of — I’m a cardiologist, we got a major shortage of contrast media because, again, we had market consolidation and one of the two companies with most of the market had to shut down its plant in China, which is making its entire supply for the US, which meant that if you came out with a heart attack or a stroke, finding a contrast or an angiogram was hard to do.

And there’s a special component of this that relates to food that I think is worth knowing about. Infant formula is complicated. Right? It’s over 30 ingredients that have to be there in a specified amount, because you’re trying to simulate mother’s milk which is, you know, developed over generations to be sustaining of infants who need to grow and thrive. Many of those natural ingredients are in short supply. Some of them come from the Ukraine in predominance and so the Defense Production Act has had to be used multiple times to divert raw ingredients into the infant formula supply. That is just a sign that we do have vulnerable supply chains at this point.

CNN: Are there are there a couple of items that you could point to that are particularly vulnerable?

Califf: Right now, it’s infant formula. Sunflower oil is one that we talk about, quite a bit.

CNN: Sunflower oil?

Califf: Ukraine.

You don’t normally think about international war being a cause of disruption of supply of food in the United States, but you know, we’ve become a global supply chain system. So, we’ve got to develop approaches that allow us to predict and preempt these things, and that’s a big part of what we’re trying to convince Congress would be helpful.

CNN: Given what’s going on in the world, and particularly with the war in Ukraine, there’s no guarantee that the American people won’t see this kind of crisis with another highly important consumer item? It could happen?

Califf: Yes, and it could happen with other commodities, too. I mean, remember, we almost had a railroad strike and that would have had a huge impact on you know, getting commodities from Point A to Point B at the right time. We’ve become accustomed to having what we want just in time. And the stores are used to keeping their stocks at a at a lower level because of the just in time system. It is a very efficient system until something goes wrong, which is why we really need an information hub for all these things to coordinate. Each of the companies has very sophisticated data about its own supply chain, but there is no master system that puts them all together and seeing what the totality would look like, so when something goes bad with one of them, like the Abbott situation, the system is not prepared to deal with it.

CNN: When you say yes, of course this could happen with other commodities too, after this year with the baby formula crisis, is the government at least is on a pathway, does it have a plan or is better equipped now to at least try to prevent this from happening?

Califf: Yeah, here’s what I’ll tell you. … So, I think the most under-heralded — of course I would always say the FDA is the most under-heralded, but other than the FDA — the most under-heralded part of the government system during the pandemic has been a supply chain effort, which involves all parts of government. And they deal with things every single day that require coordination by the government with enormous needs for communication across all the different federal entities to get the right stuff to the right place at the right time. You remember that toilet paper and all the other things where there were problems. Keeping that going and pre-empting shortages has been a huge effort that I don’t think it’s gotten enough credit or attention.

Obviously, when something goes wrong, like with infant formula, it gets a lot of attention. And that’s understandable. But successes go unheralded, because, you know, you sort of assume that things ought to work. There are a lot of people working on this. So, the knowledge is there. What I’m concerned about is that the industry by and large, and all of the industries who would regulate the supply chain as commercial confidential information, that’s part of a competitive society, is part of a competitive edge. If you have a better supply chain in your company than a competing company, that’s an advantage and they don’t want to fork over that information.

CNN: Have you spoken directly to President Biden about the baby formula issue?

Califf: I’ve not. I’ve talked a lot with Ron Klain. So, I have not spoken with the President about it, and I feel like I very much have direct line of communication with Ron Klain when needed and I think he communicates pretty well with the President.

CNN: When the President said earlier this year that he wasn’t aware of the seriousness of the baby formula issue until around April, that was surprising for some people to hear. Do you have any insight into why it was around April that he was told about the gravity of the situation?

Califf: Well, again, I’ll remind you, as I said, there are — the supply chain team was working on multiple potential vulnerabilities and if you followed the in-stock rates and other metrics, it really wasn’t till about April that things really started to change. So, I think I think they were monitoring a bunch of stuff and they likely brought it directly to his attention when it — when the numbers started to change in a significant way. That’s my best take on it.

CNN: What do reporters covering the baby formula issue really need to know or that you think they misunderstand? And separately, for parents and families and caregivers — anything you would really want them to hear from you?

Califf: Well, first of all, with regard to parents and caregivers … I’m a grandfather and I have grandchildren and I’ve had children myself. We at the FDA are very aware of the difficulty this has caused for families, and we want them to know that we’re working hard until we get things back to normal and will continue to work hard to deal with it, every single day.

With regard to reporters, I think right now, there are two big, maybe three big issues that I hope the reporters will pay attention to. The first is explaining to people about this SKU consolidation issue. Just because there are empty spots on the shelves doesn’t mean that there’s not enough infant formula and that is not an easy concept to get across. In fact, the in-stock rates that so many people quote, is not actually a measure of the amount of formula available compared to the amount that used to be available. It’s a measure of the number of types of formula available. It’s different. It measures something different than what most people think intuitively when they look at the number.

So, that’s one thing because I think it’s really important if there is enough formula that people buy what they need and not feel the need to go out and over-purchase, which … may create shortages for other people.

The second thing is when I said about the supply chain in general. I think it’s fair for reporters to ask the question, what’s the right degree to which the government should have access to supply chain data? I don’t really care if it’s the FDA or some other entity, but you … can go to the National Academy of Science Report on supply chains and see why it’s so important that we deal with this issue.

And the third one as you know, as the supplies get up, it’s time to pivot to the question of: How do we prevent this from happening again? And we got this market consolidation and several other factors that are in play that we need to come up with policies that are likely to make the system more resilient, one of which, of course as I’ve said is being able to monitor the supply chain so that we can have reserve and stock and backup plans for facilities and all the things that didn’t exist before.

CNN: Did you ever think that as a cardiologist, you would be a baby formula expert by October 2022? Has that been an unexpected experience for you?

Califf: Well, you know, when I was commissioner in 2016, I learned that every day as commissioner, you come in and you hear about something you’ve never heard of before and need to deal with. But this was definitely not on my radar when I was going through confirmation, that infant formula would be the single thing that took up the largest amount of my time. But that’s the job — it’s wherever the problem is, to work on it. We’re fortunate to have a lot of experts here at the FDA that one can rely on, and the commissioner has a particular role. And I had a chance yesterday to actually do some cardiology discussion and it was kind of nice to talk about something where you’re the expert as opposed to the hundred other things that I need to deal with.

I would also just make the point that the process of science and policy is something that’s generalizable. So, everybody’s an expert in something but in jobs like this, you need to be able to span the horizon.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2022 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.